Rugby World Cup 1995 I Samoans break Andre Joubert's hand but not his Springbok spirit

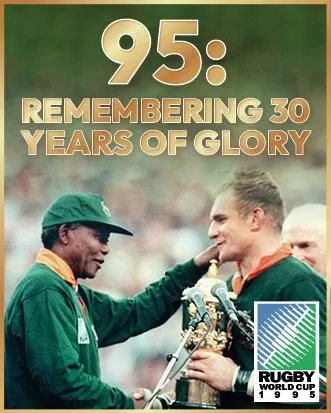

Rugby World Cup 1995

Andre Joubert was nicknamed the 'Rolls Royce of fullbacks'. Photo: Independent Media

Image: Independent Media

“Sometimes I could feel the bones moving but there was little pain.”

Those were the understated words of Andre Joubert after he had miraculously played a 1995 Rugby World Cup final and semi-final with three broken bones in his left hand.

Joubert’s Springbok coach, Kitch Christie, put his modest fullback’s achievement into a superman perspective.

“The guy is not human. I cannot believe such bravery,” said Christie.

Typically, Christie was economical when it came to lavishing praise on his players in public, so that was a telling statement.

Rugby World Cup 1995 | In retrospective

Image: Independent Media

Just seven days before the Boks’ semi-final against France, the team had played a quarter-final against the rugged Samoans at Ellis Park. Ten minutes into the game, Joubert had run past wing George Harder. The wing had shot out a fist in frustration — straight into Joubert’s left hand.

Later, the severity of the injury would be revealed but, amazingly, Joubert had the hand strapped and continued playing, only to be laid out 10minutes later in a high and late tackle by Samoa fullback Mike Umaga.

This time he came off. At 11pm that night Joubert had an operation to repair the shattered hand. Recovery from such an injury is usually seven weeks, but South Africa needed Joubert to play again in seven days. Joubert, at 31, was playing the best rugby of his career and was crucial to Springbok ambitions.

To speed up recovery, and to give Joubert a chance of playing against France, doctors suggested that he have sessions in a decompression chamber, which simulates conditions deep under the sea. Wearing an oxygen mask, he would sit in the chamber for two-and-a-half-hour sessions (he had three of them that week).

Joubert’s teammate, Mark Andrews, spent two of the sessions with him. (Andrews had suffered a rib injury against the tough-tackling Samoans.) The two were able to chat to each other — albeit in amusingly high-pitched tones. It helped alleviate the crushing boredom.

“We sat in this steel cylinder for these lengthy sessions while they lowered the pressure and pumped in oxygen, which helped reduce the swelling,” Joubert recalled.

“It would have been quite an ordeal if I had not had that walking encyclopedia, Mark, along to keep me entertained. He talked, and I listened.”

The treatment made a difference and when a special rubber sleeve was flown in from Ireland, Joubert was as good to go as could be expected. The reason the protective glove came from Ireland is that in their unique sport of hurling (a form of hockey) hands often get struck.

After Joubert had completed his treatment in the hyperbaric chamber, he held a press conference. The SA Rugby Football Union CEO at that time, Edward Griffiths, told this amusing story: “A smiling Joubert told reporters how he had been the equivalent of 14m below water but had seen no fish (Joubert is an avid fisherman). Two Japanese rugby writers earnestly recorded this marine observation in their notebooks.”

Joubert duly took his place in the starting XV for the semi-final where his hand was tested repeatedly as the French hoisted the ball into the heavens on that rainy afternoon. He came through unscathed and went on to be rock solid for the Boks in the final.

It was later that year that Joubert would be christened with his famous nickname, and fittingly it was at the home of rugby, Twickenham. England were still smarting from their early World Cup exit in South Africa and were hungry to prove themselves against the world champions. But on a crisp autumn afternoon, they had no counter to a Springbok team inspired by Joubert in a class of his own.

He was elegance personified as he glided through the England defence. He was beautifully balanced under the high ball and never flustered.

When the Boks had well-beaten their hosts, and Joubert had collected the Player of the Match award, Jack Rowell, the England coach, gave praise where it was due: “Andre Joubert is the Rolls-Royce of fullbacks.”

It may have taken an Englishman to coin a name that has stood the test of time, just like those magnificently crafted automobiles, but when it comes to South African rugby, there will always be only one Rolls-Royce.

Mike Greenaway is the author of best-selling books The Fireside Springbok and Bok to Bok.

Related Topics: