‘The University of Durban-Westville: Classrooms of Memory’

Triumph of the human spirit

Student protest meeting. From left: Jerry Coovadia, Zac Yacoob, Rector SP Olivier, and Ramlal Ramesar.

Image: Supplied

BLURB

The recent book on UDW, edited by Saleem Badat and Goolam Vahed, comprising an important collection of articles, takes us all the way to the College at Salisbury Island and then into the lecture halls of UDW. The book captures the mood, the edge of a university that was born at the height of apartheid but educated students to think beyond its racial boundaries.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.. - Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

THESE familiar words capture the very heart and essence of the chapters in this collection – narratives that go to and fro, filled with lament for the incalculable injustices that humans may inflict on their compatriots, through the systems and structures they engineer and, at the same time, narratives that embody the triumph of the human spirit and the adamant refusal to succumb to the deliberate evisceration of critical intellectual labour, in a particular place and time.

This South African story – of a historically black university (HBU) that was birthed in an obscure, discarded military barracks on Salisbury Island in the Durban Bay and began its first academic year in 1961 (three years before the Rivonia Trial, when Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela would be incarcerated for 27 years on Robben Island) and developed into the University of Durban-Westville (UDW) – belongs to all who live in this beloved country and beyond.

It is not surprising that the term "bush college" was used – ironically, deprecatingly – to intimate that the location, creation, rationale, ethos and curriculum of the HBUs in South Africa were all calculated to induce the miniaturisation of mind and of spirit. While these chapters, on the one hand, bemoan the calculated paucity of academic life measured out in the teaspoons of apartheid rationing, they also celebrate the claiming of an intellectual largesse and robustness that defied all expectation.

Indeed, the enigmatic but incisive coinage – at the edge – captures well the diverse meanings of living under apartheid, in general, and the world of the "bush colleges", in particular, as these chapters portray. On the one hand, it connotes living on the periphery – the apartheid margins – in all its precarity.

The "heart" of the campus, showing the pond, quad, cafeteria and MH Joosub Hall (far left), and library.

Image: Supplied

Official photographs of Durban show Salisbury Island, literally, off the map of Durban. And UDW, on the border between Durban and Westville, has been described as a separate township, with lights, on a hill. At the same time, "at the edge" encapsulates the incisive critique, vibrant creativity and passionate on-the-ground scholarship that assiduously emerged on these perimeters – as so many of these chapters so eloquently show.

Yes, paradoxically, "bush colleges" were built for obsolescence, directly and indirectly. The pernicious policy of separate development – and in the university sector, in this example, with its intended gulag spatial arrangements, hierarchical, monolithic structures, curricula and pedagogy – contained the very seeds of its own destruction.

Reading these accounts, each an engrossing journey into the hinterland of a part of South Africa’s past, the words, uttered in 1965, when Salisbury Island was into its fourth year of existence, by that great and inimitable civil rights activist, Martin Luther King Jr, resound across land and sea: "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

The new campus being built in Westville.

Image: Roshen Kishun

Against the measured, nuanced, critical and informative background and context that the editors themselves provide of the University College for Indians, which was inaugurated in the early 1960s on Salisbury Island, Durban, and the world of UDW that developed from it, the different contributors to this collection, writing in engaged and engaging Bildungsroman mode, and traversing this particular HBU landscape in a particular place and time, paint grounded, embodied, elegiac testimonios of their own intellectual and political journeys from a variety of perspectives.

These intrepid travellers here, into the antique land of the "bush college" that was Salisbury Island and, later, UDW, tell of the grotesque and shattered visages of the past, as much as of the beautiful ones not yet born. The landscape of memory is rugged, as we remember differently, subjectively, selectively, with competing versions of the past.

Critical reflections around the curriculum demonstrate how the intended pacification of the "natives", through the prescribed institutional culture and curriculum actually induced, in many instances, stirrings towards the obverse, as fundamental epistemological questions – Whose knowledge? What is knowledge? – inevitably surfaced and were constantly grappled with.

Ferreting out crevices and fissures in the curriculum, to forge alternative ways of knowing and being, emerged slowly but conscientiously and morphed into full-blown, bold, paradigmatic challenges in many instances, creating, in the process, vibrant alternative centres of excellence, which in time would be appreciated and recognised locally and globally.

The book cover.

Image: Supplied

The institution, beholden, in the mould and manner of "separate development" and "own affairs", to offer "culturally appropriate", "Indian" subjects – and, sometimes, clothed in a dubious Orientalism – actually served, in some instances, to develop a critical corpus of knowledge, especially in otherwise marginalised fields, and this forged, in the process, tacit alternatives to Eurocentric dominance in epistemological formulations of the curriculum.

Steering between the Scylla of Western hegemonic underpinnings and the Charybdis of ethnocentric scholarship, critical, creative, contextual, intellectual work in a variety of fields was forged, albeit falteringly initially. This contributed, serendipitously, to making UDW a unique space in the constellation of higher education institutions in the country and beyond, for a flourishing of fusion initiatives, as in music, dance, drama and art.

The insertion of critical, grounded research on Indian indenture in South Africa into historical studies as a whole – where such study was to be seen not as an appendage, but as an integral part of South African history and, indeed, reconstituting and reshaping it – was an important historiographical development.

In a tendentious move, Salisbury Island was officially established on November 1, 1960 – fifteen days before the centenary of the arrival of Indians in South Africa. As the threat of repatriation to India, which hung as a sword of Damocles for decades, was lifted at this time, it was patently clear that the "gift" of this "bush college" was a timeous Trojan horse. Provocatively, and presciently, the title of Durban writer Ansuyah Singh’s novel Behold the Earth Mourns – written to mark this centenary – captures the mood of the times.

The narratives in these chapters tell of impulses towards complicity and of defiance, narrow cultural chauvinism, as well as intellectual ferment, reflecting the multiple and competing universes on the campus. Transitioning from the sedate lectures halls to the visceral politics of the UDW Quad – which epitomised, simultaneously, the police state that South Africa was and the revolutionary uprisings and insurrections that defined and marked the decades of apartheid living in South Africa – staff and students understood only too well the daily existential perils and possibilities on UDW terrain.

It behoves us to remember that from the time of the inauguration of HBUs in South Africa, there were concurrent, signpost events in the political life of the country, such as Sharpeville in 1960, the Soweto uprising in 1976, the assassination of Steve Biko and the banning of the Black People’s Convention and several student associations in 1977.

Student leaders such as Strini Moodley and Saths Cooper, from Salisbury Island, were expelled and, later, incarcerated on Robben Island. Ironically, the inauguration of "bush colleges" across the country, as Neville Alexander has observed, served to deepen and broaden the radicalisation of students, which contributed, in no small measure, to the mounting resistance to apartheid structures.

We also do well to remember that these decades of the "dry white season" in South Africa were marked by ground-breaking changes on the rest of the continent and beyond – changes that would influence activists in South Africa directly.

From Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1962) to Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) to Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1986), these germinal texts became lodestars for "bush colleges" in their call for a revisioning of politics and history, curriculum and pedagogy – and continue to challenge us in our ongoing journey towards a more robust decoloniality.

The chapters, from across the spectrum – from managerial and administrative leaders to teaching staff and students – also show the changing scenarios over the decades. Although the post-1994 era in South Africa ushered in and promised dramatic changes, not all was triumphal. We read of the undulating histories of the institution – the victories as well as the setbacks – that attended the post-apartheid era… Global imperatives, the enticement of the market, the changing economic terrain and the merger with the University of Natal influenced the lifespan of some departments, with some flourishing and some creative spaces being terminated.

In conclusion, in the larger cartography of struggle in South Africa, these chapters speak to the important challenges we have faced, and continue to face, as we live with and negotiate the past. Confronted with the burden of history in our time and place, remembering is a sacred ritual of restoration, of reparation…

Simultaneously, such recuperation has colossal personal and collective reverberations in the syntax of rebuilding our fractured selves, fractured nation, fractured world. Against the history of the barbarism and dehumanisation that ‘bush colleges’, with their heinous tribalisms, connoted, we have to accelerate the quest for a truly non-racial, raceless society…

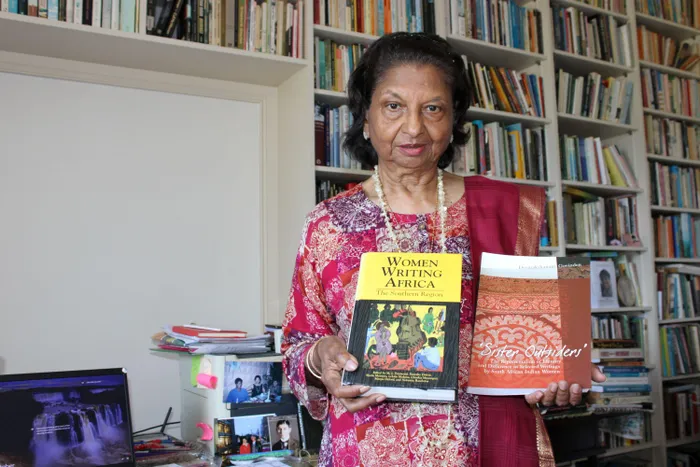

Betty Govinden

Image: Nadia Khan

Betty Govinden is an Honorary Research Associate at the School of Social Sciences at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

* This is an extract from the book University of Durban-Westville, 1961–2003. Undoing Apartheid, Building Non-Racial Culture, edited by Saleem Badat and Goolam Vahed (Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press, 2025). The editors are planning a second volume and invite former students, academics and support staff to contribute a chapter on any topic of their choice. Submissions may include critical reflections on UDW’s academic programmes, student and staff activism, student life, sport, cafeteria life, community engagement, or any other topic that comes to mind. Send a topic and abstract of 150 words to [email protected] by September 27.

Related Topics: